Edward Sheriff Curtis was a visionary. His vision defined his work. Literally. Fortunate that he was passionate about his work, he was equally unfortunate that his work — his passion — cost him his marriage and his family. Like another one of my favorite visionaries, Antoni Gaudi, (a relative contemporary of Curtis) whose magnum opus remains incomplete half a world away, Curtis had wealthy benefactors that backed his project. Both men died in poverty, nonetheless. I’ll talk about Gaudi and his art nouveau movement on a different occasion, but I mention him here because both men were innovative thinkers ahead of their time. Culturally different though they were, Curtis and Gaudi probably would have made good friends. Language barrier aside, I think there would have been no obstacle to understanding the scope and breadth of one another’s ideas. They were both game-changers. Game-changers in the sense that because of them, how we perceive culture and history is irrevocably different than before. We are responsible for the vision they have shared with us. We can’t ignore it, turn away and pretend we didn’t see it. In fact, we cannot help but respond to it. It changes us.

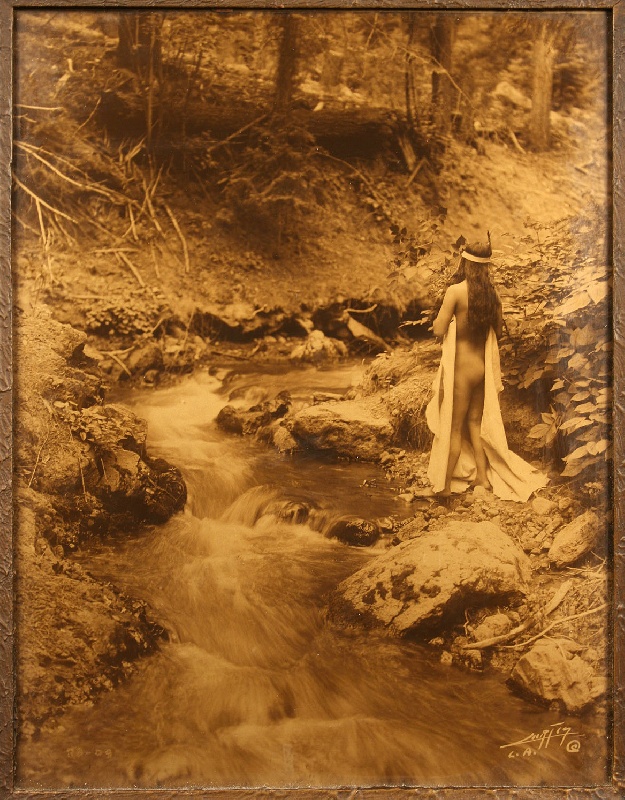

And that is what happens in Chapter Two: Awakening of House Key. Among other historic artifacts that capture Jordan’s attention in the MacRae library is the enignmatic portrait of an unknown Native American woman. Jordan responds to the soft golden glow that emanates from the image itself. Her mother, Deirdre, later correctly identifies the portrait as a rare “orotone” that could have been executed by none other than Curtis himself. Though he did not invent the process of creating orotones (oro meaning gold in Spanish from the Latin aurum), Curtis perfected the technique which required extreme precision and careful execution. The process is best described in an article, “A Discussion of Orotones” published by Claire Hoevel of the Indianapolis Museum Art (IMA) Conservation Department in the museum’s blog two years ago.

The article discusses the process pertaining to two IMA acquisitions, “Three Chiefs Piegan,” 1900, and “The Vanishing Race,” 1904. The latter strikes me as particularly relevant to a departure scene Evangeline describes in a journal entry toward the end of House Key. “The Vanishing Race” depicts Native Americans riding away from us on horseback toward a vanishing point in the horizon. The feeling of resignation and humility intensifies through the golden glow that gives the piece a noble dignity, nonetheless. Could Curtis have achieved the same effect using the photogravure process invented in 1879? Perhaps, but you decide.

Photogravure involves chemically etching a photographic image onto a copper plate, cleaning it, applying ink to the plate, and then printing individual prints on paper. Like other photographers of his time, such as the renowned Alfred Stieglitz, Curtis produced an incredible body of work using photogravure. However, his orotones involve a more complicated process whereby the negative image is projected onto a glass surface pre-treated with emulsion to create a positive image when developed and fixed. The next step is what makes Curtis’s orotones so distinctive: He used an amyl acetate solvent mixed with a synthetic cellulose nitrate lacquer that produces what is referred to as “banana oil” due to its strong smell. It serves as a liquid means of applying a powered mix of copper and zinc across the image. Masterfully applied, it that gives the image its uniquely luminous quality. The glass, then backed with paper and framed, intensifies and preserves the vibrant quality of the image.

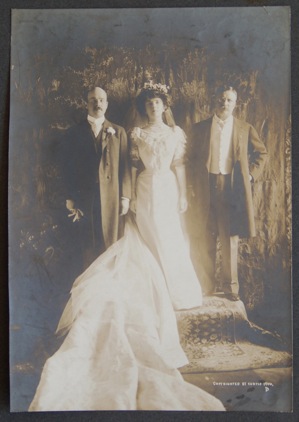

So, it should come as no surprise that Jordan is drawn to, and enchanted by, this special treasure protected in a secret library. The quandary is that Curtis was not known to have worked east of the Mississippi. He did, however, photograph the inauguration of President Theodore Roosevelt, and even the wedding of his daughter, Alice, in 1906. That at least puts him in the vicinity of when the MacRae portrait may have been taken. Hold that thought for when we get back to the portrait in the sequel of House Key.

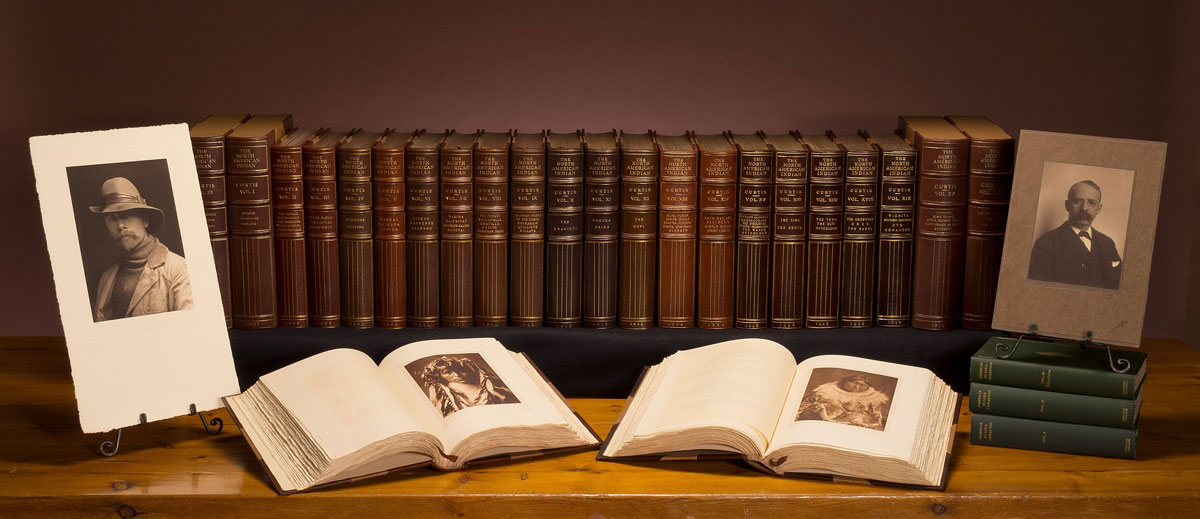

Meanwhile, let’s consider the other discovery Jordan makes in the library, something as rare as the orotone portrait itself: A 20-volume set of leather-bound books entitled, The North American Indian. The last volume was published in 1930, containing images and essays of Curtis’s 30-year odyssey to capture the cultural essence of a people doomed to obscurity and near-anihilation. These books contain over 2,200 photogravures of an estimated 40,000 taken of approximately 80 tribes, and 4,600 written pages. Curtis chose the finest paper available for printing his volumes, just as he did with his photographs. Those of us obsessed with photography, printing and publishing will be interested to know that his papers of choice were a Dutch etching stock called Holland Van Gelder, and for his books, Japanese Vellum.

Even by today’s standards his was an ambitious project. Crowd-funding wasn’t a thing back then, but Curtis managed to get 195 subscribers for an edition of 500 of his multi-volume ethnography. Backed by influential patrons who had the wherewithal to help fund Curtis’s vision, such as J.P. Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt, the project still went over-budget and missed its projected deadline by 25 years. Collectors are aware of 272 sets that were printed of the originally intended 500, one of which happened to end up in the MacRae library. Still, Jordan has no idea that, according to expert, Selby Kiffer, Senior Vice President of Sotheby’s Book and Manuscript Department, a set sold for $80,000 about 20 years ago, and a complete set today is valued at between $400- and $500,000.

Though Curtis died broke, we still owe him for having recognized the imminent demise of Native American culture and its people as American expansionism increased. Relentless is sharing his vision, he endeavored for the greatest part of his career to record images of Native Americans for posterity, and through these images, tell their stories. He is quoted as having said, “The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other; consequently, the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting one of the greatest races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time.” Though his original printed photographs and books are rare, we are fortunate to live in a digital age in which we can still access images of his work. Curtis would probably be happy to know that a complete set of The North American Indian has been digitized by Northwestern University and is only a click away. Acknowledging his contributions in House Key, and hoping you will check out his work after reading this, is my small way of saying, “Thank You.”

Leave a Reply